Measuring Empowerment : The Importance of Indicators

Author:

Curated by: Ayesha Pattnaik

How could a woman’s agency and empowerment be best measured while taking into account local contexts and the various understandings of what constitutes empowerment? Women’s empowerment is typically mentioned as an aim or effect of projects focused on gender equity and discrimination. However it is rarely studied on its own, and largely discussed in terms that do not enable comparison with women’s experiences of empowerment across contexts.

OneStage’s CEO, Dr. Nivedita Narain, has worked extensively on women’s empowerment in rural India. One of her projects, EMERGE, has developed an index to measure and study individual empowerment of women, with a focus on women’s experiences of public participation and collective action. Her research explores a relevant question for practitioners today: how can the empowerment of women be tangibly measured, in order to foster inclusive governance and effective policymaking?

The EMERGE Project

The Evidence-based Measures of Empowerment on Research on Gender Equality (EMERGE) project began with an aim to address the lack of data on collective action and political participation in rural India particularly. The project leverages existing community level structures and innovative methods in order to create tools that can measure types of community-based collective action; as well as women’s public participation and under-representation in politics.

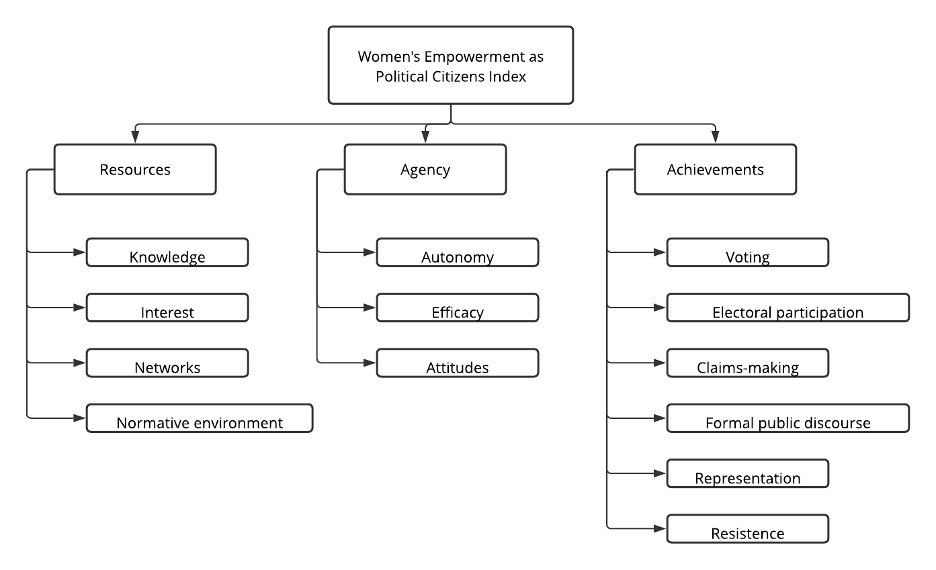

The team developed a set of survey questions to construct a single measure of an individual woman’s political empowerment, called the Women’s Empowerment as Political Citizens Index (WEP Citizens Index). The index comprised 30 questions drawing on Kabeer’s research that posits the study of political empowerment needs to evaluate the ability of women to influence social change at three levels: resources, agency, and achievements. The surveys were specifically designed for the context of rural India, which are aggregated and weighted such that each of the three main domains receives equal weight.

To evaluate the WEP Citizens Index, two surveys were conducted in Betul district of Madhya Pradesh, India in 2019. The final measure for each individual is an empowerment score that ranges from zero to one.Both surveys included all component measures of the index and were conducted with a random sample of adult women from rural villages. The first survey was conducted as per usual academic surveying practices with a team of external surveyors and included 540 women from 12 villages. The second survey was conducted as per a common practice of practitioner organisations and employed community-based data collectors (CDC) to survey 756 women from 16 villages, overlapping the 12 villages from the first survey.

Key Findings

To measure women’s ability to influence change across the three domains of resources, agency, and achievements – the team came up with a variety of indicators that could capture each aspect. For instance, resources was not only measured through material and economic factors, but also including knowledge and norms that circumscribe action. Agency is a particularly interesting indicator as it proposes a novel way of going beyond available resources to understand the individual’s beliefs and abilities to shape their own decisions, such as through questions about autonomy. Finally, achievement focused on all the various outcomes that demonstrate engagement and change in institutions. This not only includes more visible actions like engagement with the state, but even increased voice and claim-making in public discourse.

This in itself is a major contribution of this measure: by defining empowerment as multi-faceted, it allows scope to identify the ways in which women are empowered. Recognising this agency of women is crucial, particularly in surveys that want to build on empowerment. Instead, these findings help us understand what is left to achieve for complete empowerment. The figure reveals a similar distribution for the two surveys are similar in shape and spread, as shown in the third panel of the figure. This implies that the WEP Citizens Index is a reliable measure.

The figure below summarises findings across the surveys. Overall, there is a large spread of political empowerment across women, varying from 0.03 to 0.90. The average political empowerment score was 0.4 in the external enumerator survey and 0.35 in the CDC survey. This score implies that on average, women are not as entirely disempowered as other surveys may indicate.

Roughly 13% of women score below 0.2, which means they have at least a few components of one domain of either resource, agency, and achievement, and lack empowerment in the other two domains. For example, a woman at this score could have knowledge of and interest in elections and political issues, but no agency to make choices about political participation.

This highlights another key advantage of this measure- it allows us to conceive of the various kinds of interventions required to boost empowerment. This survey reveals that for instance, a woman could have all of the resources needed to mobilise for their goals, and some agency over this ability to participate. However, without increased knowledge, they would eventually not utilise these resources and therefore have a lower score of empowerment.

Lessons for Studies of Empowerment

A key part of all projects is assessment of impact, and this is where developing holistic indicators is essential for being able to understand and analyse change. This study provides a detailed analysis of the multi-faceted nature of women’s empowerment and how identifying multiple indicators can ensure it is effectively measured.

These indicators are understudied and absent in most surveys and activities, which instead focus on simple social indicators. In particular, voice and agency of participants are rarely measured and instead changes in material circumstances are recorded. This practice frames them more as recipients rather than active agents.

Development is incomplete without a nuanced understanding that not only looks at how communities are affected by change, but also the opportunities they have to participate in setting the agenda. This project urges us to ensure assessment systems make room for analysing the space for voice and participation, in order to ensure a more holistic understanding of empowerment is part of our agendas.

For more details, read about the EMERGE projecthere.

.png)

.png)